As Stoic Tengrists, here at the Society, we typically refer to Tengri as “the Source” or “the Originator.” Many cultures throughout history have been able to invent (or rather discover, depending on how you would like to see it) unique words to refer to a singular supreme being that is the creator of the universe. Mankind has come up with numerous terms to define the One – the one true God who is one with the cosmos, the starter of time and space, and sometimes its controller as well.

Ancient and Classical Languages

- Hebrew (Judaism)

- YHWH (יהוה): Often referred to as the Tetragrammaton, this is the personal name of God revealed to Moses. It is considered too sacred to be spoken aloud, and is often replaced with “Adonai” (Lord) in reading. Yahweh, Yehovah, Jehovah, Yahu (as in Yahudi) are words that stemmed from the Tetragrammaton.

- Elohim (אלהים): Though plural in form, it is often used with singular verbs to refer to the One God. Nonetheless it is a plural word and many scholars believe that in the Old Testament, the Jewish Scripture, the Elohim is in fact used to describe a group of beings. Some scholars, particularly those who study the early history of Israelite religion, suggest that “Elohim” might reflect an earlier polytheistic context where multiple gods were worshiped and over time, this evolved into the monotheistic worship of YHWH. There is a concept of a divine council in ancient Near Eastern texts, including some passages in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., Psalm 82), where “Elohim” could refer to a council of divine beings with YHWH as the chief deity. This aligns with some interpretations of “Elohim” as a collective term for gods or divine beings. It is also important to note that some researchers suggest that early Israelite religion was in fact henotheistic, meaning they worshipped one god (YHWH) without denying the existence of other gods. In this view, YHWH could be one of the “Elohim” who made a covenant with the people of Israel.

- Hashem (Hebrew: הַשֵּׁם haššēm, literally “the name”; often abbreviated to ה׳ [h′]) is a title used in Judaism to refer to God.

- El Shaddai (אֵל שַׁדַּי): Often translated as “God Almighty,” this title emphasizes God’s ultimate power and sufficiency.

- Greek (Christianity)

- Theos (Θεός): Used in the New Testament to refer to God. (More on the significance of Theos in relation to contemporary Tengrism and its understanding of the cosmos below.)

- Kyrios (Κύριος): Meaning “Lord,” used to denote the authority and divinity of God.

- Pantokrator (Παντοκράτωρ): Translated as “Almighty” or “All-powerful,” it emphasizes God’s omnipotence.

- Aramaic (Christianity)

- Abba (אבא): An Aramaic term meaning “Father,” used by Jesus to express a close, personal relationship with God.

- Latin (Christianity)

- Deus: The general term for God in Latin, used in the Vulgate Bible and Christian liturgy.

- Arabic (Islam)

- Allah (الله): The Arabic word for God, used in the Quran to refer to the One God. Even though the nname Allah is widely regarded as a special sacred name that presented itself to humanity through vahiy and gospel, it is critical to note that it is a compound word that stemmed from El / Al ilah, literally meaning “the God”, as ilah is likely a version of Eloh. Assyrian Christians has the word Elaha or Alaha, a direct relative of the Syriac Alaha. In Maltese we see Alla. In Aramaic the equivalent would be Elah.

Ancient Near Eastern Languages

- Akkadian

- Anu: The supreme god of the sky, often associated with the highest deity in the pantheon.

- Ilum: A term used for God, similar to the Hebrew “El.”

- Sumerian

- An: The sky god, considered the highest deity.

- Egyptian

- Amun-Ra: Combining Amun, the hidden god, and Ra, the sun god, into one supreme deity.

South Asian Languages

- Sanskrit (Hinduism)

- Brahman: The ultimate reality or world soul, representing the singular, universal spirit.

- Ishvara: A term for God or supreme being, used in various philosophical contexts.

East Asian Languages

- Chinese

- Shangdi (上帝): Meaning “Supreme Deity,” used in ancient Chinese religion.

- Tian (天): Meaning “Heaven,” often personified as a deity or the divine will.

- Japanese (Shinto and Buddhism)

- Kami (神): While generally referring to gods or spirits, it can also denote a supreme deity in certain contexts.

- Amaterasu: The sun goddess, often considered a central deity in Shinto.

Indigenous and Pre-Colonial Cultures

- Aztec

- Ometeotl: A dual-gendered deity representing the unity of opposites, considered the supreme god.

- Inca

- Viracocha: The creator god who fashioned the world and all living beings.

- Norse

- Allfather (Alföðr): A title used for Odin, representing the chief and creator god.

- Yoruba (West Africa)

- Olodumare: The supreme god, creator of all things and source of all energy.

Modern and Contemporary Contexts

- English

- God: The term widely used in Christian contexts and general discourse to refer to the supreme being.

- French

- Dieu: The French term for God, used in Christian contexts and everyday language.

- German

- Gott: The German term for God, used in Christian contexts and common parlance.

Understanding the Greek Word “Theos” (θεός)

The Greek word “Theos” (θεός) holds a significant place in the lexicon of ancient Greek language, philosophy, and theology. Its usage spans from classical literature to the sacred texts of Christianity, shaping its multifaceted connotations and theological implications. This article delves into the nuances of “Theos,” addressing its meaning, its relationship with Chaos and Cosmos, and its role in Abrahamic scriptures.

1. Does “Theos” Mean “a god” or “the God”?

The term “Theos” in ancient Greek can refer to both “a god” and “the God,” depending on the context. In polytheistic Greek religion, “Theos” was used to denote any deity within the pantheon, such as Zeus or Athena. The indefinite use signifies one among many gods.

However, in philosophical and monotheistic contexts, “Theos” often takes on a more definitive role. For instance, in the works of philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, “Theos” can signify a supreme being or an ultimate principle underlying reality. This more abstract and singular usage aligns closer to the concept of “the God” in monotheistic traditions.

2. Is Theos the Opposite of Chaos, and If So, What Is Cosmos?

In Greek mythology, “Chaos” (χάος) refers to the primordial void or the state of nothingness from which the first gods and the universe emerged. “Theos,” on the other hand, represents the divine entities that brought order and structure. In this sense, “Theos” can be seen as an antithesis to Chaos, as the gods imposed order on the chaos, leading to the formation of the Cosmos (κόσμος).

“Cosmos” in Greek means “order” or “world,” and it refers to the ordered universe created by the gods from the initial state of Chaos. Therefore, while “Theos” is not necessarily the first spark before the order of Cosmos is formed, the gods (theoi) collectively are responsible for transforming Chaos into Cosmos, establishing a harmonious and structured universe.

3. Theos in the New Testament and Its Relationship to YHWH

In the New Testament, written in Greek, “Theos” is predominantly used to refer to the one true God of the Abrahamic tradition. This usage aligns with the monotheistic belief in a single, all-powerful deity. The New Testament writers adopted “Theos” to communicate the concept of God to a Hellenistic audience, bridging the gap between Jewish and Greco-Roman understandings of divinity.

For example, in the Gospel of John, the opening verse states: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God (Theos), and the Word was God (Theos).” Here, “Theos” unequivocally refers to the singular, supreme God, consistent with the monotheistic doctrine.

The use of “Theos” in the New Testament differs from the tetragrammaton YHWH (יהוה), the specific and sacred name of God in the Hebrew Bible. YHWH is a personal name revealed to Moses, representing God’s eternal and self-existent nature. “Theos,” while also referring to the same God, serves more as a title or descriptor rather than a personal name. The New Testament occasionally bridges this gap by using titles like “Kyrios” (Lord) to convey the authority and divinity of YHWH in a manner accessible to Greek-speaking audiences.

Etymology of “Tengri”

- Old Turkic Origin:

- The word “Tengri” comes from the Old Turkic “𐱅𐰭𐰼𐰃” (Tengri), which means “sky” or “heaven” and by extension “God” or “the Sky God.” In the context of Turkic shamanism, Tengri is the supreme god of the sky, overseeing human fate and nature.

- Mongolic Languages:

- In Mongolic languages, “Tenger” refers to the sky or heaven and is also used to denote the supreme deity. This similarity suggests a shared cultural and linguistic heritage between the Turkic and Mongolic peoples.

Connections to Other Languages

- Chinese Influence:

- Some scholars suggest that the word “Tengri” might be connected to the Chinese word “天” (tiān), which means “heaven” or “sky.” The Chinese concept of “Tiān” also encompasses the idea of a celestial power or deity, similar to Tengri. The phonetic similarity and conceptual overlap point to possible cultural exchanges along the Silk Road and other contact points between ancient Chinese and Central Asian cultures.

- Indo-European Connections:

- There are speculations about possible connections to the Proto-Indo-European root *dyeu-, which means “to shine” or “sky, heaven.” This root is the origin of various words for gods and sky in Indo-European languages, such as the Latin “deus” (god) and Sanskrit “dyaus” (sky, heaven). However, the connection between Tengri and the Indo-European root is more speculative and less direct compared to the clearer links with Turkic and Mongolic languages.

Historical and Cultural Context

- Tengrism:

- Tengrism is the shamanistic and animistic religion that centers around the worship of Tengri. It was the predominant belief system among the early Turkic and Mongolic tribes. Tengri is seen as the eternal blue sky, the ruler of all spirits, and the provider of stability and order.

- Modern Usage:

- In contemporary Turkic and Mongolic societies, the term “Tengri” still holds cultural and spiritual significance. It appears in various cultural expressions, place names, and even in modern adaptations of ancient beliefs.

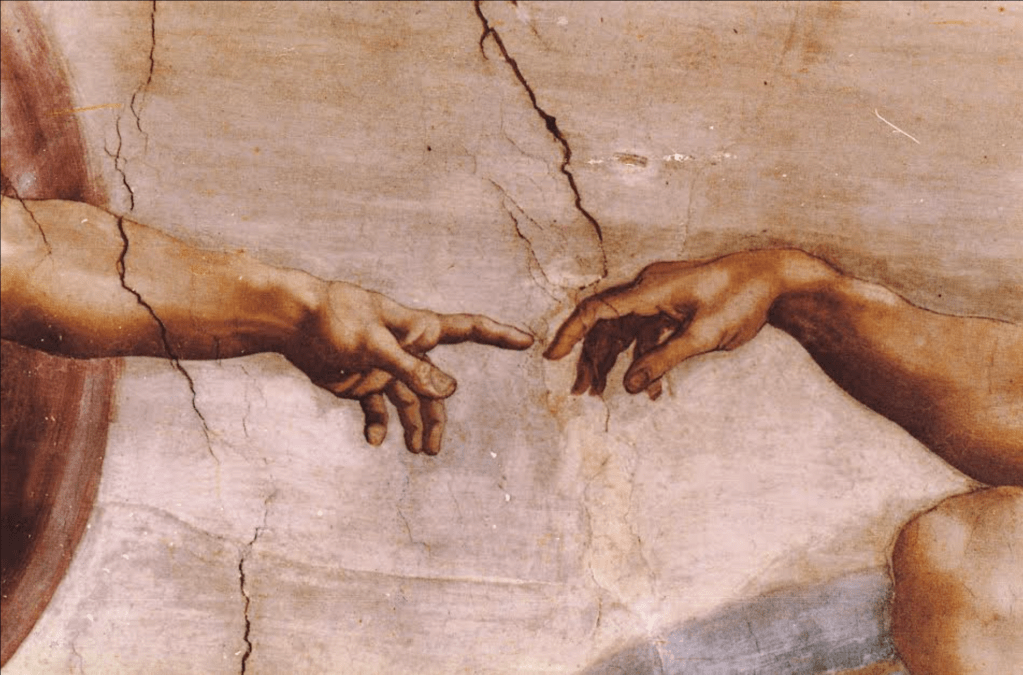

The Big T: Theos, Tengri and the Big Bang

In the context of ancient Greek thought, “Theos” (θεός) can be analogized to the concept of the Big Bang as the primordial catalyst that transitions the universe from a state of chaos to an ordered cosmos. This notion aligns “Theos” with the fundamental spark that initiates the creation and organization of time and space, embodying the force that brings coherence to the primordial disorder. Such a portrayal of “Theos” not only reflects the ancient Greek understanding of divinity as the architect of order but also resonates with contemporary interpretations in cosmology, where the Big Bang signifies the commencement of the universe and the genesis of spacetime. Interestingly, this conceptualization finds a parallel in modern Tengrism, where Tengri, the Sky God, is envisioned as the entity that instigates the formation of the universe through a cosmic event akin to the Big Bang. In both traditions, the divine figure—whether Theos or Tengri—serves as the prime mover, orchestrating the emergence of the structured universe from the void, thereby establishing a profound link between ancient theological narratives and contemporary cosmological theories.

The Tengrist Society © 2025