Why the Universe Might Just Be God, and God the Universe

There is a moment when one lies beneath a starry sky, the enormity of the cosmos pressing down, stirring a sense of profound wonder. Call it the Universe. Call it Tengri.

In order to perceive the concept of God in Stoic Tengrism one must try to se the big picture. The biggest, in fact. Tengri is not your typical mythological humanoid deity. It does not resemble the thunderbolt-wielding Zeus or the patriarchal figure of monotheistic traditions. Tengri is an all-encompassing force, as eternal and expansive as the blue sky from which its name derives. For the Turkic and Mongolic peoples who invoked Tengri, the divine was not distinct from the world; it was the world—sky, earth, stars, and all that lies in between. Imagine seeing God not above you but around you, within you, and interwoven with every particle of existence.

Fast forward a few millennia, and modern science adds an intriguing dimension to this ancient worldview. Enter the Big Bang theory, the scientific narrative of the Universe’s origins. Picture this: 13.8 billion years ago, an infinitely dense point of light burst forth, giving rise to galaxies, stars, planets, and everything we now know—including us. If we consider Tengri as being everywhere and everything emerging from that primordial explosion, then it follows that the stars above, the ground beneath, and even the molecules in your coffee are manifestations of Tengri. The cosmos, then, is not merely surrounded by God; it is God. Or Tengri. The distinction dissolves.

This idea, though ancient, is far from obsolete. The Stoics of antiquity articulated a remarkably similar concept through their notion of Logos. For the Stoics, Logos was the rational principle that ordered the Universe, governing everything from the motion of the stars to the workings of the human mind. Logos is both divine and imminent, a force that permeates the cosmos. To live a virtuous life, the Stoics argued, one must align oneself with Logos, embracing one’s place within this rational and harmonious whole. Living according to nature, then, was not merely practical but sacred.

What does this mean for us today? What sort of an alternative deism does Stoic Tengrism offer? It offers a transformative perspective on how to view the world not as a random assembly of elements but as a sacred and interconnected whole. To live in accordance with the Universe is thus living in accordance with Tengri, it is to embrace one’s role in the cosmic order. It invites humility, for we are part of something far greater than ourselves. It cultivates gratitude, as each breath we take is a participation in the life of the Universe. And it fosters resilience, reminding us to flow with the natural rhythms of existence.

Spinoza’s Concept of “God or Nature” and Its Relation to Stoic Thought

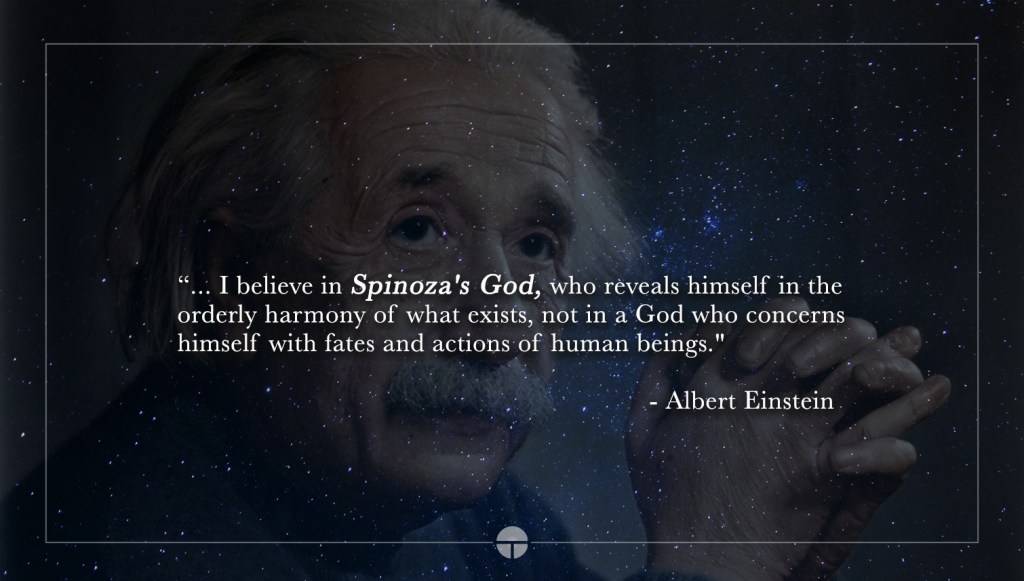

Baruch Spinoza, a 17th-century Dutch philosopher, is often credited with one of the most radical redefinitions of God in Western philosophy. His famous notion of “Deus sive Natura” (“God or Nature”) stands at the heart of his metaphysical and theological thought, especially in his magnum opus, Ethics. Spinoza’s conception of God departs from traditional theistic views and converges on an immanent, naturalistic interpretation of divinity, which resonates with certain elements of Stoic philosophy. Both Spinoza and the Stoics believed in a universe governed by rational principles, and they viewed divinity as embedded within the structure of the natural world.

***

Interestingly, this perspective is not far removed from the ideas of Baruch Spinoza, the 17th-century philosopher who famously equated God with nature. For Spinoza, God was not a supernatural being but the substance of the Universe itself, encompassing all that exists. His vision of a pantheistic God aligns seamlessly with the idea of Tengri as the cosmos, suggesting a divine presence inherent in the very fabric of reality.

Spinoza’s God: Substance, Immanence, and Necessity

For Spinoza, God is not a transcendent creator who exists outside the universe, as traditional religious views would assert. Instead, Spinoza equates God with Nature (or the whole of existence). In Ethics, Spinoza presents a rigorous, geometrically inspired philosophy that begins with defining God as the only substance that exists. According to Spinoza, everything else in the universe—whether it be physical objects, minds, or abstract ideas—exists as a mode or manifestation of this single substance.

Spinoza’s view of God as synonymous with Nature signifies that God is not a personal, anthropomorphic deity. Rather, God is the underlying reality of everything—eternal, infinite, and governed by immutable laws. In this sense, God is immanent, meaning that God is present in every part of the universe and does not stand apart from it as a separate entity. Spinoza also posits that all events in the universe occur out of necessity. This deterministic framework denies the possibility of miracles or divine interventions, as everything follows from the immutable laws of Nature, which are identical to the laws of God.

Stoicism and the Unity of God and Nature

The Stoic philosophers, particularly those of the Hellenistic period like Zeno of Citium and Chrysippus, developed a pantheistic worldview that also equated God with Nature. For the Stoics, the universe is pervaded by a divine, rational principle called Logos, which governs everything according to reason. Like Spinoza, the Stoics rejected the idea of a personal, interventionist god and embraced a worldview in which divinity is intrinsic to the cosmos.

In Stoic cosmology, everything that exists is part of a unified, rational order, and all things unfold according to divine law, or Fate. The Stoic God is, in essence, identical to Nature—a force that is simultaneously rational and providential. The Stoic universe is both material and divine, as they believed in a form of “corporeal monism,” where even the soul and reason are corporeal substances, though finer than physical matter.

Spinoza’s Deus sive Natura mirrors this Stoic understanding in several ways. Both systems advocate for a rational, unified universe, governed by necessary laws. In this sense, Spinoza’s God, who is indistinguishable from Nature and the source of all things, shares with the Stoic Logos the function of being the rational order underpinning reality.

Divergences in Spinoza and Stoic Cosmology

While Spinoza’s views echo Stoicism, there are significant divergences between the two philosophies. One major difference lies in their conception of the nature of divinity. The Stoics believed that God (or Logos) was a material substance, akin to fire, which actively organized the cosmos. In contrast, Spinoza’s God, while intimately involved with the natural world, is not conceived in material terms. For Spinoza, God is the one substance that has infinite attributes, two of which are thought and extension (the material world). This means that while physical reality is an expression of God’s essence, God itself transcends physicality in a way that Stoic Logos does not.

Furthermore, Stoicism maintains a teleological view of the universe. The Stoics believed that the rationality of the cosmos ensured that everything happened for a reason and for the ultimate good of the whole. Spinoza, on the other hand, rejected teleology. According to Spinoza, Nature (or God) does not act with any purposeful goal in mind. Rather, everything happens according to the deterministic and necessary laws of Nature, without reference to any overarching purpose or final cause. In this regard, Spinoza’s view is more mechanistic, aligning more with the scientific materialism of his time than with the Stoic belief in providence.

Ethics, Freedom, and the Human Condition

Despite their metaphysical differences, both Spinoza and the Stoics emphasized the importance of understanding the nature of the universe to attain a sense of ethical freedom and tranquility. For the Stoics, living in accordance with Nature meant accepting the divine order and embracing one’s fate with equanimity. Since everything that happens is an expression of divine reason, the Stoic sage cultivates apatheia (freedom from emotional disturbance) by accepting whatever befalls them.

Spinoza offers a similar view of human freedom, though he couches it in the context of his deterministic universe. For Spinoza, true freedom is not the ability to act outside the laws of Nature (which is impossible) but rather the intellectual understanding of those laws. When humans understand the necessary causes of things, they can come to terms with their place in the world and achieve a kind of peace. This intellectual love of God (amor intellectualis Dei), for Spinoza, is the highest form of blessedness and mirrors the Stoic ideal of living in harmony with the rational order of the cosmos.

Conclusion: God and Nature, Rationality and Ethics

Baruch Spinoza’s Deus sive Natura articulates a vision of God that is deeply connected to the natural world, similar to the Stoic conception of divinity. Both philosophies emphasize a rational, ordered universe governed by necessary laws, where God is not an external creator but rather the essence of all that exists. Spinoza and the Stoics offer different frameworks for understanding human freedom and ethical life, but they share a commitment to the idea that knowledge of the universe and its laws leads to wisdom and tranquility. By equating God with Nature, both philosophies challenge traditional religious conceptions and offer a vision of divinity as integral to the fabric of reality itself.

Read more about “God” in Stoicism.

The Tengrist Society © 2025